Body Armour

Introduction

Body armour was limited in all cases to Thracian nobles and commanders, ie Thracian heavy cavalry, until the introduction of mail shirts for infantry with the Roman client-kingdom. There were two basic types, from northern and southern Thrace. Thracian armour was characterised by local alterations and conservatism, with some types of armour persisting long afer they ceased to be used elsewhere. Initially, the armour was made of leather and/or bronze, but iron armour started to appear in the fourth century.

Early armour

Front and

two rear views of a thin bronze Thracian cuirass from 5th

c. B.C tomb in Eski Saghra (Stara Zagora) Bulgaria, as displayed in the

Ashmoleum Museum. Photographed by the author with a digital camera

through the display glass without a flash.

Front and

two rear views of a thin bronze Thracian cuirass from 5th

c. B.C tomb in Eski Saghra (Stara Zagora) Bulgaria, as displayed in the

Ashmoleum Museum. Photographed by the author with a digital camera

through the display glass without a flash.

Museum accession number 1948.97 Bronze Breast plate, one iron rivet still attached to left shoulder & remains of rivets round the edges, patched with bronze in the middle inside. H.354m W.288m

Museum

accession number 1948.98 Bronze Back plate with remains of iron rivets

round edge one bronze patch at bottom of left shoulder blade H.336m

W.315m

Left: a later bell

cuirass, from A Fol, Thrace and the Thracians

Left: a later bell

cuirass, from A Fol, Thrace and the Thracians

A model of a Thracian noble wearing a bell cuirass; a photograph from another web site sent by Daniella Carlsson. Right: A drawing of a fifth century bronze bell cuirass from Rouets (Archibald, fig 8.1, p198). A unique feature of the Rouets cuirass is the semicircular extension or mitre to protect the abdomen, still attached by means of silvered nails to the bottom of the breastplate. A Greek cavalryman's armour was heavier than a hoplite's (Xenophon Anabasis 3.4.47-9), so this feature may actually have been more common than is generally realised.

|

|

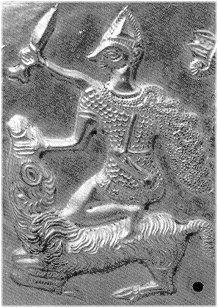

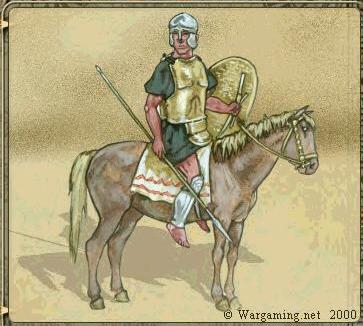

Greek armour was imported into Thrace at least from the sixth century; "bell" corselets have been found, apparently still in use in Thrace in the fifth century when they were obsolete in Greece itself. Corinthian, Attic, and other helmets, and greaves also crop up. These pieces seem to have been restricted to chiefs, and often only one or two pieces are found in a grave, rather than a complete panoply. The result must presumably have been that the chieftains in question appeared n a rather motley mixture of Thracian and Greek equipment. Figure 14 represents a reconstruction of what one such might have looked like. He wears normal Thracian dress and weapons, but adds to them a Corinthian helmet and a bell-corselet, both found in Thracian graves of the fifth century. The abdominal plate fastened to the lower edge of the cuirass is an oddity, because it is generally a Cretan defence, though a few are known from mainland Greek sites; the finding of one in Thrace is most surprising. When Xenophon records his service in Thrace towards the end of Anabasis we get the first suggestion of actual bodies of armoured Thracian troops; he records the cavalry of Seuthes "wearing their breastplates" (Vll.3). This probably represents an armoured bodyguard rather than suggesting that all Thracian cavalry we're armoured. We can get an idea of the appearance of these cavalry from a series of plaques of about this date, (Fig. 15). The rider's legs and arms are textured with fine criss-cross lines in a style used in similar plaques to represent cloth, so he may be a northerner dressed in Scythian-influenced style; the plaques come from Letnitsa, vvhich may have been in Triballian territory. Nonetheless I have shown my reconstruction of a heavy cavalryman in short-sleeved tunic only, the more common Thracian style of dress which would be worn elsewhere. The plaques show scale corselets, divided into pteruges below the waist, in Greek style. But they are not Greek corselets, assuming they are accurate representations, because they lack shoulder-pieces but appear to have short sleeves.

Figure 19: Possible appearance of a Thracian heavy cavairyman, late 5th or 4th century plus the Aghighiol greave and helmet, and the saddlecloth taken from the Kazanluk paintings. Figure 19 represents the possible appearance of a Thracian noble heavy cavalryman of this period. He is based on Figure 15; the Aghighiol-style greave is inspired by that plaque, the helmet by its association with the greave. Possible alternative equipment would include boots or Kazanluk-style shoes in place of the greaves; an odd cuirass described by Hodinott (page 93) and found in a Getic grave of c. 300 BC, "made up of iron strips, some decorated with small bosses within embossed circles, linked by tiny rings; it appears to have been decorated by a small snake made by silver wire." There was also available a whole range of helmets. (text and pictures by Duncan Head) |

Left and above: from Thrakische Kunst, plates 112-115

Кираса из Фракии. Click on the top left-hand corner to see the decorations.

Left: "Brustpanzer", Items 189 and 190 from Gold der Thraker, heights 32cm and 39cm respectively. Archaeological Museums Kazanluk Inv. No. 497, and Sofia Inv. No 3364, respectively. Click for a closer look.

� Protective armament, bronze, end of

6th-4th century BC. Helmet - Tchelopechene, Sofia district; armour -

Ruetz, Turgovishte district; greaves - Assenovgrad district. The hemet is

of Corinthian type with outlined openings for the eyes. The armour is

three-part. The upper two parts are decorated with relief stripes which

present the muscles stylized. The third one is attached through hooks and

protects the lower part of the body. Its parts are jointly connected which

allows it to be used by horsemen. A unique feature of the Rouets cuirass

is the semicircular extension or mitre to protect the abdomen, still

attached by means of silvered nails to the bottom of the breastplate. The

greaves are shaped anatomically and bear the producer's seal. No. 68 from

the Sofia National History Museum guide.

� Protective armament, bronze, end of

6th-4th century BC. Helmet - Tchelopechene, Sofia district; armour -

Ruetz, Turgovishte district; greaves - Assenovgrad district. The hemet is

of Corinthian type with outlined openings for the eyes. The armour is

three-part. The upper two parts are decorated with relief stripes which

present the muscles stylized. The third one is attached through hooks and

protects the lower part of the body. Its parts are jointly connected which

allows it to be used by horsemen. A unique feature of the Rouets cuirass

is the semicircular extension or mitre to protect the abdomen, still

attached by means of silvered nails to the bottom of the breastplate. The

greaves are shaped anatomically and bear the producer's seal. No. 68 from

the Sofia National History Museum guide.

Click to see a close-up of the breast-plate ("erhaltene H�he 35cm") and mitre from Gold der Thraker, item 192, which places it 450-400 BC. Archaeological Museum Sofia Inv No. 6168

�Right: an inaccurate picture of a Thracian noble from DBA Online, showing how uncomfortable this armour would have been to wear on horseback, with that flap bouncing up and down all the time!

North Thracian Armour

Thracians are usually depicted on metalwork wearing scale armour. This was a common form of protection in the Near East and it was probably from thence that the Skythians aquired it. The Thracians may have adopted this fashion through their contacts with the steppe peoples or directly from the Near East. The use of Skythian-derived militaria, particularly arrowheads and akinakai, makes Skythia the likely choice. Scale armour became more common over the fourth century. It was as flexible as the leather cuirass with pteryges worn by Greek cavalrymen, and in principle offered better protection.

Left: two of the Letnitsa plaques, mid-fourth century BC, pp 164-169, Ancient Gold

�Plate B from the Osprey book

"The Skythians" shows a dead Thracian noble (B3), wearing scale

bronze armour and typical Thracian helmet.

�Plate B from the Osprey book

"The Skythians" shows a dead Thracian noble (B3), wearing scale

bronze armour and typical Thracian helmet.

� Plate D: Skythian warriors (D1 and D2) wearing armour strikingly similar to that shown above

Text for Skythian images from The

Skythians 700-300 BC by Dr E V Cernenko & Angus McBride, Osprey

Men-at-Arms Series, London, 1986

B3: Thracian Warrior, 4th Century BC

D1: Fully-armoured warrior, 5th century BC

D2: Fully-armoured warrior, late 5th/early

4th century BC

The following is from ZH Archibald, The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace, pp 197-201, reproduced by kind permission of the author.

Body armour

is rare even in graves from central Thrace, although it is also rare in tombs

from coastal Macedonia and Chalcidice, which clearly does not correspond with

real-life equipment (Thucydides 2.100.5). The Odrysian cavalry of

Seuthes II certainly wore breastplates (Xenophon, Anabasis 7.3.40).

Six surviving examples of Thracian body armour are oddly retarded

compared with the goods they accompany...only one can be dated, to around the

turn of the fifth century...These primitive cylindrical pieces make few

allowances for comfort and ease of movement. The armholes are rather

sharp and a pronounced waste band with rolled edges projects outwards at the

lower end. On the Tatareveo cuirass, the pectoral and shoulder muscles

ended in simple three-petalled lotuses, with fishe's tails added to the

former. On the Turnichene and Svetlen corselets, the breast muscles have

become engraved marine monsters, ketoi, whith other anatomical details

enhanced by seven- and nine-petalled palmettes. The ketos here

is the typical monster of Korinthian art, with a long snout, snapping jaws, and

spikey mane. The three-petalled lotus is still found on metalwork of the latter

half of the sixth century... [the three curiasses are dated to the second half

of the sixth century or the first half of the fifth, and they were made outside

mainland Greece].

Body armour

is rare even in graves from central Thrace, although it is also rare in tombs

from coastal Macedonia and Chalcidice, which clearly does not correspond with

real-life equipment (Thucydides 2.100.5). The Odrysian cavalry of

Seuthes II certainly wore breastplates (Xenophon, Anabasis 7.3.40).

Six surviving examples of Thracian body armour are oddly retarded

compared with the goods they accompany...only one can be dated, to around the

turn of the fifth century...These primitive cylindrical pieces make few

allowances for comfort and ease of movement. The armholes are rather

sharp and a pronounced waste band with rolled edges projects outwards at the

lower end. On the Tatareveo cuirass, the pectoral and shoulder muscles

ended in simple three-petalled lotuses, with fishe's tails added to the

former. On the Turnichene and Svetlen corselets, the breast muscles have

become engraved marine monsters, ketoi, whith other anatomical details

enhanced by seven- and nine-petalled palmettes. The ketos here

is the typical monster of Korinthian art, with a long snout, snapping jaws, and

spikey mane. The three-petalled lotus is still found on metalwork of the latter

half of the sixth century... [the three curiasses are dated to the second half

of the sixth century or the first half of the fifth, and they were made outside

mainland Greece].

The other three corselets..., also belong to the 'bell' type, but of a more advanced form, anatomically better adapted with more deeply cut armholes. The waist band has disappeared, as has the upstanding collar; the anatomical relief lines are more carefully modelled... A unique feature of the Rouets cuirass is the semicircular extension or mitre to protect the abdomen, still attached by means of silvered nails to the bottom of the breastplate.

The later group is unique in having rather deep neckholes. A piece of iron sheet still attached to the left shoulder of the Bashova cuirass, extending into the neck area, and traces of iron have been detected at 2-3cm intervals near the edge, on front and back. Similar traces of iron have been found at the same location of the Rouets and Dulboki models, again especially marked on the left shoulder... these were the vestiges of iron-backed collars, similar to the lunate pectorals or gorgets with gilded silver veneering known from fourth-century warrior burials.

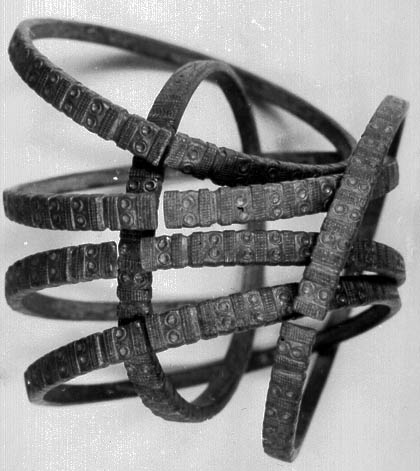

A warrior buried in central Thrace did not have the usual corselet. Instead he had an iron belt composed of a broad strip made of iron scales, curving upwards at the top and originally fixed to some organic substance, either leather or linen. A similar belt was found in Bashova Mogila. It is not clear whether such a belt would have been worn below the metal cuirass found in the tomb, or as an alternative to it. Such belts were used in Greece prior to the introduction of the metal breastplate, but they were common in western Asia and continued to be used by the Skythians (note the belt on the Skythian warriors above) and in various parts of of the Achaemenid empire. Archibald (p198) says the armour of the mounted warriors on the Lovech silver gilt belt is leather armour with pteryges. The design of this belt recalls Uratian bronze belts of around 600BC, so it may be that Thracian warriors wore something similar. It is possible that groups of gilded silver appliqu�s found in fifth century Thracian tombs were originally attached to a leather parade corselet, similar to the later iron corselets from Vergina and Prodromion. Another warrior buried near Lovech wore a leather jerkin with a belt to which were attached thongs for a scabbard, fixed with a bronze ring decorated in the native animal style with a reclining doe.

Later armour

Left: Alexander III

wearing a composite corselet.

Left: Alexander III

wearing a composite corselet.

Duncan Head says: [this] bronze plate cuirass is a late improved

version of the "bell" type, a variant worn in Greece at the beginning

of the 5th century, but found in Thrace till the middle of the 4th. Unlike the

early bell cuirass, this style has only a narrow out-turned flange at the

waist, and instead of a high collar to protect the throat, the neck is cut low

leaving the upper chest exposed. Unlike Greek examples, which were worn with

pteruges probably attached to an undergarment, the Thracian cuirasses have a

row of holes along the edges to take a lining, and this probably indicates they

were worn without pteruges. The exposed throat and upper chest were covered by

a crescent shaped gorges of silver-plated gilded iron, decorated with bands of

relief ornamentation; it has an upstanding collar to protect the throat, and a

narrow hinged strip fastens round the back of the neck. The collars seem to

have stayed in use longer than the cuirasses, as two examples date from the

second half of the 4th century (from the Maltepe tumulus and Vurbitsa), and a

gorges of similar shape and date, but of bronze scales on leather, comes from a

Macedonian grave. These examples are not associated with cuirasses, and in fact

it is not at all clear what armour was worn when the late bell style went out

of fashion. One grave (1st century BC, from Beroe south of the Balkan

mountains) produced scale armour, but generally this was confined to the north

(next figure). Possibly linen or leather cuirasses were worn (there are earlier

examples of metal fittings for Greek-style non-metal cuirasses) or perhaps the

Hellenistic cavalry muscled cuirass, though no traces of this type survive.

Zosia Archibald (pp 255-256) continues (text and images reproduced by kind permission of the author):

As in Skythia, the composite metal cuirass, made of iron scales or strips

fastened with bronze rings to a leather backing, continued to be worn in

conjunction with bronze

or other metal armour... In tumulus I at Kyolmen some of the 238 fragments showed

the imprint of woven fabric on the back, perhaps linen... One of the most

significant finds of such scale armour comes from a well-furnished woman's

burial in tumulus IV at Kyolmen. An iron scale pectoral composed of small

plates of iron arranged in rows perpendicular to a semicircular reinforced rim

lay at the skeleton's feet. In shape, technique, and dimensions (30 cm in

diameter as reconstructed) this recalls the silver gilt iron pectoral found at

Mal tepe near Mezek...and...semicircular

bronze

or other metal armour... In tumulus I at Kyolmen some of the 238 fragments showed

the imprint of woven fabric on the back, perhaps linen... One of the most

significant finds of such scale armour comes from a well-furnished woman's

burial in tumulus IV at Kyolmen. An iron scale pectoral composed of small

plates of iron arranged in rows perpendicular to a semicircular reinforced rim

lay at the skeleton's feet. In shape, technique, and dimensions (30 cm in

diameter as reconstructed) this recalls the silver gilt iron pectoral found at

Mal tepe near Mezek...and...semicircular  sheet

gold collars, probably reinforced with iron. The Mal tepe collar [shown

at right and left- plate 100 from Hoddinot- its surface silvered with traces of

gilding] also had traces of fabric on the reverse. Each pectoral was

composed of a semicircular iron crescent fixed at the back with some form of

catchplate, fitted closely aroud the neck by means of a low upstanding

collar. The surface was veneered with thin sheets of gilded silver

decorated with concentric bands of mainly vegetal ornament. The

association of such parade collars with iron body armour was strengthened

by the discovery of a very similar pectoral in a Macedonian soldier's burial

near Katerini, Piera (fig 10.11) which now has a very close counterpart from an

unlooted tomb near Makrygialos. The most sumptuous example... is the

gorget of sheet gold from the antechamber of tomb II at Vergina. The

Katerini collar was worn over a composite cuirass decorated with gilded silver

appliq�s. The Vergina equipment included a separage, undecorated iron

collar, and iron helmet, and the iron cuirass found in the main burial chamber,

decorated with sheet gold ornaments (gorgoneia and lions' head masks).

The development of iron sheet body armour seems especially connected with

Macedonia under Philip and Alexander. Iron helmets of Phrygian from,

like that from Pletana, can likewise be associated with a Macedonian source.

sheet

gold collars, probably reinforced with iron. The Mal tepe collar [shown

at right and left- plate 100 from Hoddinot- its surface silvered with traces of

gilding] also had traces of fabric on the reverse. Each pectoral was

composed of a semicircular iron crescent fixed at the back with some form of

catchplate, fitted closely aroud the neck by means of a low upstanding

collar. The surface was veneered with thin sheets of gilded silver

decorated with concentric bands of mainly vegetal ornament. The

association of such parade collars with iron body armour was strengthened

by the discovery of a very similar pectoral in a Macedonian soldier's burial

near Katerini, Piera (fig 10.11) which now has a very close counterpart from an

unlooted tomb near Makrygialos. The most sumptuous example... is the

gorget of sheet gold from the antechamber of tomb II at Vergina. The

Katerini collar was worn over a composite cuirass decorated with gilded silver

appliq�s. The Vergina equipment included a separage, undecorated iron

collar, and iron helmet, and the iron cuirass found in the main burial chamber,

decorated with sheet gold ornaments (gorgoneia and lions' head masks).

The development of iron sheet body armour seems especially connected with

Macedonia under Philip and Alexander. Iron helmets of Phrygian from,

like that from Pletana, can likewise be associated with a Macedonian source.

Mal Tepe pectoral (found with a man and the fittings of a chariot), 350-300 BC, 21 cm wide, its ends ornamented with spirals and scales. The central part has two rows of women's heads, althernating with other bands ornamented with geometrical and plant designs. This pectoral was part of an iron cuirass. (right-hand picture is item 318 from the 1976 British Museum catalogue, National Archaeological Musuem Inv. No. 6401). From the Maltepe mound near Mezek, Haskovo district. Click to see the colour picture (from Thracian Treasures from Bulgaria, the British Museum catalogue). The Skythian king is from Plate G of the Osprey Men-At-Arms book "The Skythians" by E V Cernenko; it shows how the pectoral might have been worn.

Left:

From L'Armure des Thraces, in Archaeolgia Bulgarica 3/2000, p13

.

Left:

From L'Armure des Thraces, in Archaeolgia Bulgarica 3/2000, p13

.

Gold strips and

studs from Panagyurishte, as well as six quadrangular silver appliques with the

head

Gold strips and

studs from Panagyurishte, as well as six quadrangular silver appliques with the

head  of Apollo and

two low-relief silver discs showing Heracles and the Nemean lion, could have

belonged to a composite outfit...The pectorals... were designed to be manifest

symbols of rank. The Katerini burial provides a date not later than the

middle of the fourth century for the appearance of the advanded form of iron

pectoral with sheet metal inlay. The other four were deposited in the

last third of the century.

of Apollo and

two low-relief silver discs showing Heracles and the Nemean lion, could have

belonged to a composite outfit...The pectorals... were designed to be manifest

symbols of rank. The Katerini burial provides a date not later than the

middle of the fourth century for the appearance of the advanded form of iron

pectoral with sheet metal inlay. The other four were deposited in the

last third of the century.

Iron-backed collars seem, on present evidence at least, to have had a longer tradition in Thrace. The eclectic style of decoration on the fourth-century pectorals draws on familiar metropolitan Greek motifs on one hand...and Thraco-Macedonian sources on the other... The Thracian pectorals form a sub-group within the series. The introduction of one-piece iron-backed pectorals coincides with the earlier examples of iron cuirasses of the Classical period at Vergina and Prodromion. At Gaugamela Alexander wore an iron helmet and gorget (Plut Alex 32.5), quite probably of the same type as these pectorals.

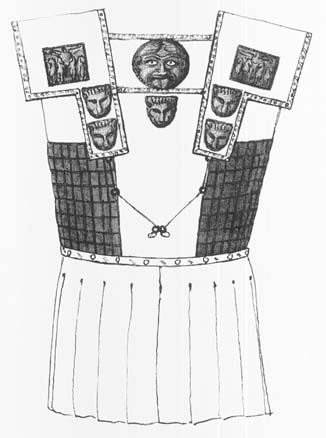

Above: the armour of Philip II or Alexander's half-brother, Philip III Arrhidaios. A similar suit of armour has been found in Thrace, of which only the golden lions' heads survive.

Left: Five silver gilt plaques for a

cuirass, height 5.5cm, Plovdiv Museum Inv No 1652, from Golyamata Mound,

Douvanli, c.450 BC. Click for a closer look. (I have repeated the same

photo five times)

Left: Five silver gilt plaques for a

cuirass, height 5.5cm, Plovdiv Museum Inv No 1652, from Golyamata Mound,

Douvanli, c.450 BC. Click for a closer look. (I have repeated the same

photo five times)

Far Left: Silver gilt plaque for a

cuirass, width 9cm, Plovdiv Museum Inv No. 1653, in the form of a Gorgon (mask of

Medusa) from Golyamata Mound, Douvanli, c.450 BC. Click for a closer

look.

Far Left: Silver gilt plaque for a

cuirass, width 9cm, Plovdiv Museum Inv No. 1653, in the form of a Gorgon (mask of

Medusa) from Golyamata Mound, Douvanli, c.450 BC. Click for a closer

look.

Left: Two silver gilt plaques for a cuirass, height 6.5cm, Plovdiv Museum Inv No. 1562, in the form of a Nike (Goddess of Victory), with wings, wearing a long chiton and mantle, standing in a chariot holding a wreath in her right hand and the reins in her left. The head of Nike is shown in profile, but the eye is rendered frontally. A ribbon binds her hair. From Golyamata Mound, Douvanli, c.450 BC. Click for a closer look. (the same photo twice).

The above plaques were all found together, with two pectorals (Plovdiv Archaeological Museum Inv 1643 and 1644) shown below. How were they worn?

Left: Dr

Ljuba ogenova-Marinova's reconstruction of these items. From L'Armure

des Thraces, in Archaeolgia Bulgarica 3/2000, p16.

Left: Dr

Ljuba ogenova-Marinova's reconstruction of these items. From L'Armure

des Thraces, in Archaeolgia Bulgarica 3/2000, p16.

Pectorals

Left: Gold crescent

shaped Pectoral from c. 5th B.C tomb in Eski Saghra (Stara

Zagora). It has three hole for suspention, decorated with embossed animal

heads & rosettes etc in rows. L.355m W. 228m. Ashmolean Museum

accession number 1948.96

Left: Gold crescent

shaped Pectoral from c. 5th B.C tomb in Eski Saghra (Stara

Zagora). It has three hole for suspention, decorated with embossed animal

heads & rosettes etc in rows. L.355m W. 228m. Ashmolean Museum

accession number 1948.96

Left: Fourth century gilded

silver collar with iron backing from Virbitsa, near Preslav. Right:

Fourth century gilded silver collar from Katerini, Pieria. Figs 10.9

& 10.11 from Z H Archibald, The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace. Fragments

of a sliver pectoral with iron backing have also been found in Yankovo, near

Preslav (see fig 10.10 in Archibald)

Left: From L'Armure des Thraces, in Archaeolgia Bulgarica 3/2000, pp13 & 14. Click for a closer view, including a side view.

The pectorals below were all found on a man's chest, in different

burials.They all have holes at each end for attachment.

Above: Gold pectoral, 33.1 cm long, width 9.5cm, early 4th century BC, Golemani, Veliki Turovo district (plate 149 from Ancient Gold)

Above: 4th century Gold pectoral, 20.5cm long, 8.2cm high, Strelcha (plate 138 from Ancient Gold)

Above: Late 5th -early 4th century Gold pectoral, 13.9cm long, Duvanli

(plate 136 from Ancient Gold)

Above: Mid-5th century Gold pectoral, 38.5.cm long, Duvanli (plate 135 from Ancient Gold, inv. No. 1643). A small semicircle is cut off from the middle of the upper part where the two ends of the garment on which the pectoral was worn met. This was found with smaller pectoral (Inv. No. 1644, not to scale, it is only 17.5 cm long) at right; each has small holes for attachment; apparently one was worn on each side of the chest (how???). Pages 90-91 of Fol, and Plate 215 of Thrakische Kunst

Above: 5th century Gold pectoral, 16.5cm long, Duvanli (plate 224 from Thrakische

Kunst and p91 from Fol)

Above: 5th century Gold pectoral, 23.4cm long, Duvanli (plate 216 from Thrakische Kunst and p91 from Fol, Thrace and the Thracians)

There are seven others -See plates 217, 218, 220, 221, 222, 223, 225 from Thrakische Kunst